How I learned to Notice - and Subvert - the Algorithms of My White Bubble

The Bubble of Whiteness turns our view upside down without us even noticing. Photo credit: Wierzchu, 123rf.com

An algorithm is like a jumping-to-conclusions machine, but one we can harness once we become aware of it.

Much has been said about the social “bubbles” we all inhabit, that allow us to echo similar sentiments back and forth, reinforcing our own cultures. Often when I facilitate workshops on dominant culture, White participants will lament that they want to get out of their bubbles but don’t know how. This is particularly true after an egregious act of racism has hit the news.

Breaking out of the White Bubble is tough - there are strong social algorithms designed to reinforce dominant White cultural norms. They hold us inside like a giant hand we can’t see; and like any lens, they can distort, limit, or hyper-focus our view. But with practice, we can learn to notice these algorithms and begin to push back on them to expand our view.

Advertising: An In-Your-Face Algorithm

I’ll never forget the day that my Pandora ad feed switched into Spanish. I was going through a Psychedelic Cumbia phase, listening to groups that mix traditional Latin rhythms and instruments with electric organ and surf guitar. I had created a station for it and would play it while working at my computer, the Spanish lyrics less distracting for me as a native English speaker. Then one day, suddenly there they were: the same insurance companies and breakfast cereals, but with Spanish text and voices. At the time I dismissed it as a funny glitch, nothing consequential but a good story: “Pandora thinks I’m fluent in Spanish!” After all, the content of the ads had not changed, just their language.

Pandora thinks I’m fluent in Spanish. . . Facebook thinks I'm Black!

Around the same time there was a Facebook post going around with directions to check and see how it categorized you for its advertisers. I followed the steps and found that Facebook thought I was a Black woman. This again seemed funny to me, and obviously wrong given that I had multiple profile photos that clearly showed my White face. I laughed and told my friends, “Facebook thinks I’m Black!” Then it occurred to me that the reason that this was happening was that Facebook didn’t think that White people would create, share or like posts about racial equity as often as I did. That’s when I first became aware of the inherent racial stereotyping in algorithms. And what I realize now is that Facebook and other platforms don't actually “think” at all. They simply aggregate a lot of data about what I like and post, and compare it with what masses of people like and post. Then they make decisions based on this, about what ads to feed us; or, who we might know or want to follow; or what similar books, music, films or podcasts we might also enjoy.

When these algorithms work, we don’t notice them

When I was listening to English lyrics and my feed was full of English-speaking ads I absolutely did not notice that correlation. I didn’t feel like I was being kept in some kind of English-speaker bubble. I simply received ads I could easily understand. And for the platform running the algorithm it’s not odd to draw the conclusion that someone listening to lots of music in a single language prefers that language. Similarly it wouldn’t be wrong to say that White people on the whole are less likely to like and post about racial equity. The problem is in the algorithm’s inability to recognize outliers - people who like me aren’t fluent in Spanish but love Latin music; or who are White but post, like and share about racial equity.

An algorithm is like a jumping-to-conclusions machine, but one we can harness once we become aware of it.

Suggested Content as "Intellectual Infrastructure"

. . these classifications form hidden “Intellectual Infrastructures” that organize how we see our world. - Emily Drabinsky, Bias in the Library

Algorithms are actually nothing new, they are just able to collect exponentially more data now. Let’s take the example of suggesting content we might like based on what we just consumed. Historically, libraries and music stores have relied on classification systems to help us browse. In the pre-streaming era I might have walked into a music store and flipped through albums (or later, cassettes or CD’s) in the Latin Music section. Browsing there I might have even found a Psychedelic Cumbia subsection and, while looking for a favorite band, would have noticed similar artists in the neighboring bin.

Algorithms in the Library

Libraries also offer us shelves of similar content to browse. You’ve probably heard of the two main classification systems, Dewey Decimal and Library of Congress, that organize which books you’ll find on which shelves. I’ve gone down many happy rabbit holes in either system as I looked for one book and couldn’t help but notice other related works on the same or neighboring shelves. Nothing biased about that, right?

White Library - Photo credit Giammarco, @giamboscar

Well, not exactly. As with algorithms, the unexamined assumptions of the creators are going to create biased systems. Both Dewey and the Library of Congress systems were developed by upper-class White men according to the norms of their times. The On the Media podcast detailed the resulting Bias in the Library last year. In the Dewey Decimal system, for instance, civil rights movements and leaders are not filed in history (900’s) but are placed into social sciences (300’s) by category: Women’s, LGBTQ, African American, etc. This means that a person looking for books on the history of the US presidency would not find anything about President Obama shelved alongside books about all the other US Presidents. Instead Obama’s story would be found in the African American Social Science area - a physical segregation of American history in the library.

"The normal is not named." - Emily Drabinski, Bias in the Library

The flipside of this is demonstrated by the Library of Congress system, developed by Thomas Jefferson, which uses subject headings rather than numbers. White-centric thinking shows up in that "the normal is not named." For instance, you can search and find Women’s history or Black history (the “exceptions”), but not White or Men’s history. Those were just “history” in Jefferson’s world view.

Redlining: Content Suggestions in Concrete

Today, our zip codes and school district zones also work as physical classification systems, creating bubbles that are more segregated than ever. Think about what you consider to be a “good” school or neighborhood, and how you know that? Where would you find a restaurant that you’d walk to or sit on the sidewalk outside of? Where might you love the food but order take-out instead? Think about who lives nearby, and how the neighborhood got that way. You’ll find that a 20th century plan, now referred to as redlining, was the white-centric classification system that now influences our browsing of locations. The excellent Race & Redlining short video from NPR Code Switch’s Gene Demby summarizes redlining, including its impact on schools, housing, policing and health care.

Classification systems, like social media algorithms, reflect the ideology of the people who designed them. Having books or albums or businesses adjacent to each other similarly directs our browsing and helps shape our internal classification systems. As pointed out by critical pedagogy librarian Emily Drabinski in Bias in the Library, these classifications form hidden “Intellectual Infrastructures” that organize how we see our world. This rings true in my experience. In the music store I knew to look for Cumbia under “Latin music” and not “popular music,” even though this genre is enormously popular worldwide. “Popular music” designates US songs that fit normative patterns of harmony, melody, instrumentation, and language. That’s the intellectual infrastructure of songs well-liked in the mainstream.

Suggested Content as Narratives of Our Identity

"Art is where associations are made. Art is where we form the narratives of our identity." - Ronald Wimberly

Similar to library classifications, algorithms also use familiar groupings in order to make it easy for the broad mainstream of people to find what they are looking for. This in itself reinforces the status quo and feeds back to influence how we see the world. Step one of breaking out of your bubble is to notice how you’re being influenced by social media.

For me, this had to happen a few times for it to sink in. There were the Pandora and Facebook examples, neither of which I thought was an important influence on my life. Then one evening I curled up on my couch to watch director Ava DuVernay’s Selma, about the historic voting rights marches from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. I was surprised to be offered a whole different set of previews than I had seen before, all featuring Black lead characters.

Some were about the history of the Civil Rights movement - an understandable link based on content - but others were independent dramas, love stories, and other unrelated genres. Most had Black directors less famous than DuVernay. The thing that classified these films with Selma was their Black casts. I realized there were interesting movies telling the stories of Black communities that I had no idea even existed because I was typically offered films with predominantly White cast members. It’s as though once I established a White-popular viewing pattern, the mold was cast. The bubble was constructed.

Then, an even more consequential algorithmic flip happened. One day I was browsing through the people offered to me as potential connections on LinkedIn and they were nearly all White. Again, that didn’t seem unusual to me, because that’s how my LinkedIn suggestions always had been. Then I saw a Black colleague and sent a connection request. The next time my suggestion page populated, it was at least half people of color. I had reached some kind of tipping point. The change in the complexion of the page was striking, and has continued ever since. Now that I’m connected to a more diverse pool, I have second- and third-degree connections to their networks and am offered even more connections to Black, Indigenous and racialized people.

The next time my suggestion page populated, it was at least half people of color.

What’s the consequence of seeing only White films or only White professional people? These form an even deeper level of our operating narratives, our racial imaginations. As Black graphic artist Ronald Wimberly puts it in his striking graphic essay, Lighten Up, "Art is where associations are made. Art is where we form the narratives of our identity." As an educator I had thought a lot about what images we were putting into the imaginations of children, both about their own future possibilities and their imaginations of others’. It strikes me now that even as an adult, I need to actively curate what narratives I take in. This includes the elaborate stories conveyed in films, books and podcasts, as well as the small professional narratives of my LinkedIn connections.

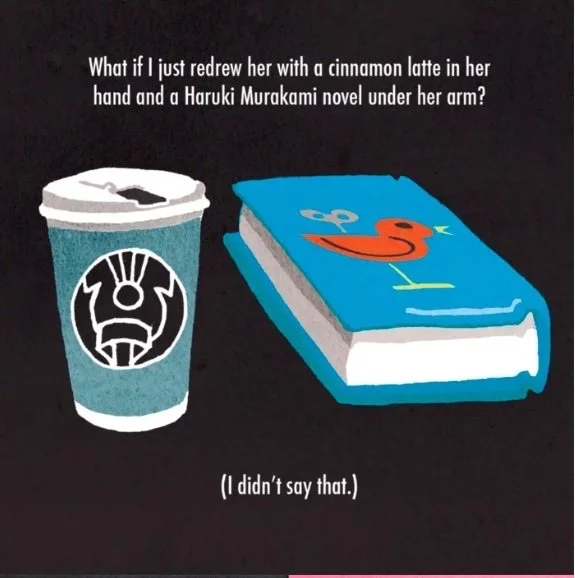

Cartoonist Ronald Wimberly suggests items associated with whiteness to his editor in Lighten Up

Consider how a LinkedIn network full of white faces and professional bios plays into hiring processes and decisions. What’s the likelihood, for instance, that this could produce the mindset that continues to hire mostly White people because “we advertised but no people of color applied.” Further, if the only Black films I’m ever made aware of are chronicles of slavery and the civil rights struggle, how can I see Black people as anything but tragic? Or, as Denise Myers questioned in the backlash to the Black Little Mermaid, “If you cannot see or accept a fictional character surrounded by talking sea creatures as Black, how the hell are you going to start to give your Black employees the opportunity to be managers, senior leaders and part of the board or even employ them in the first place?”

Bubble-Bursting 101

The White people I work with are often concerned with the double bind of their white bubbles. They want to racially integrate their lives, but often give up when they realize that changing neighborhoods or workplaces is complicated and high-stakes - especially considering the persistent outcomes of redlining. Others accept the challenge but find themselves uncomfortable and perhaps unready for the transition. Many of us find ourselves going to White doctors, dentists, and other professionals. The more white people you know, the more white people you potentially know, and the more you imagine white people filling important roles in your life. When we do decide to find a new dentist or accountant, we may only find ourselves picturing white folks in those roles. And as long as these algorithms remain invisible to us, they inhibit our developing any sense of personal accountability in the system.

Assess your big picture: Look at what your algorithms feed you.

A great place to start the important work of bubble-bursting, then, is becoming conscious of the algorithms that inform our narratives and networks. Assess your big picture: look at what your algorithms feed you. What films, podcasts, books, music and network connections are you offered? How do they influence the way you imagine connecting to people professionally? As neighbors or fellow parents in a parent association? Then look for new genres, authors, directors, etc. If you’re not sure where to start, ask an actual librarian - it’s their job to be up on a wide variety of books and media. You can also search your streaming platforms for “Indigenous films” or “Asian shows” or “Black podcast,” "Latin Music" or even "Psychedelic Cumbia." The good news is that if you keep adding people and media from outside your bubble, those algorithms will flip and you’ll be offered a wider range of people and ideas.

If you or your organization are curious about assessing your algorithmic big picture, let’s talk! I’ve got some activities to engage your curiosity and plenty of content suggestions to expand your browsing.