The Bishop, The President, and the Anatomy of a Call-On

Episcopal Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde preaching at the Service of Prayer for the Nation

I’m sure you’ve watched the sermon or at least seen the headlines by now, the ones blaring out different takes on Episcopal Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde directly addressing President Trump at the Service of Prayer for the Nation. The headline writers clearly had their thesauruses activated. Did she plead with the President? Implore? Confront or rebuke him? Call him Out? Frankly, this simple phrasing gets it right - she Called On Trump to have mercy.

As a student of Calling Out, In, On and Off, and as someone who knew Bishop Mariann Budde for years as my pastor in her former Minneapolis congregation, I can say her instinct is to offer loving accountability using a Call In or Call On. She’s definitely someone who values relationships and community. In fact, when criticized from within her denomination for holding a Service of Prayer for the Nation at the start of Trump’s first term, she replied that she was "trying to create a church where we actually speak to people who see the world differently than we do." Understanding this motivation, her sermon is a great example of a Call On, as written about by Loretta J. Ross in her forthcoming Calling In: How To Start Making Change With Those You’d Rather Cancel.

Calling Out

Let’s start by illustrating what the sermon was not: a “Call Out.” A Call Out is a public shaming for wrongdoing. It’s a grenade dropped into a physical or virtual room where the “caller” gets to turn on their heel and leave the debris to fall. It even can be anonymous. It requires no relationship, no expectation that the wrongdoer learn and grow, and no acknowledgement of their basic human dignity. It can often come from a place of pain, lashing out at the cause of the pain, or even at something that reminds us of it. Had Bishop Budde wanted to use the service as a Call Out, she would have publicly and specifically catalogued the harms she believed were caused by the President. She would have used denigrating or even dehumanizing language to describe him. The call to action would have been for her allies to boycott, un-follow, block, or otherwise punish him — with the underlying assumption that a guy like that could never change. It might have felt momentarily good to those that agree. Strategically, its value would have been, as author and thought leader Sonya Renee Taylor puts it, “saying ‘Ouch!’ loud enough that someone can hear it,” particularly when said to a person with significant power.

Calling In

The sermon was also not a Call In, though it shares some of the DNA of that method. As Loretta Ross puts it, “A Call In is a Call Out done with love.” Furthermore, a Call In requires that you believe that all of us can learn, grow, and do better. To avoid triggering defensiveness, Call Ins are typically done in private, and in an ongoing relationship. There’s an expectation of continuing the conversation over time, with both listening and truth telling. In fact, the three foundations of unity that Bishop Budde listed earlier in her sermon — respect for the dignity of every person, honesty, and humility — can also describe the conditions for successfully Calling In. But, for a Call In to work, both parties must be open to having this ongoing conversation. If you don’t have an existing relationship of warmth or trust, a Call In isn’t likely to work.

Calling On

Short of that, the next growth-oriented option is the Call On. It can be done in public or in private, as long as it communicates care for the other person and the firm belief that they can do better. This sounds easy, but when a figure has become as polarizing as President Trump, it can be hard to soften our rhetoric, and our hearts. A skillfully done public Call On also has the advantage of reassuring onlookers that you care about the situation and the people who have been or stand to be harmed in it.

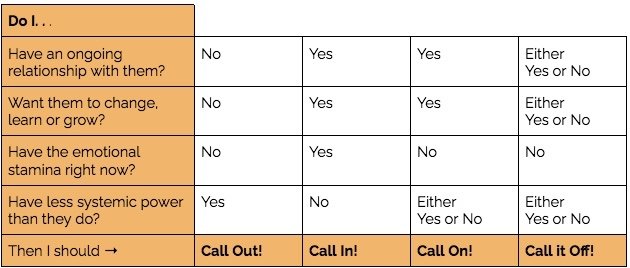

Calling Out/In/On/Off Decider

The tools and their purposes, personal requirements and power dynamics at a glance, to help you choose wisely.

So how did this particular Call On work?

Bishop Budde started by recognizing the legitimacy of the President’s win and the dignity of his followers by acknowledging nonjudgmentally that “Millions have put their trust in you.” She also connected with the President’s stated beliefs. Rather than dismissing his claim to have been saved by God during the assassination attempt last summer, she validated it. “As you told the nation yesterday, you have felt the providential hand of a loving God.” She then went on to use that belief as a place of common ground, referring to “our God.”

In doing this she also called him to his best self. This is the second vital feature of a Call On — acknowledging that the person is capable of better, and perhaps has done better in their life.

Third, she drew the distinction between the best or expected behavior and what she recently had heard him say — in this case, the President’s recent executive orders regarding queer and immigrant people. She stated a current fact, “People are scared,” rather than speculating on the future impact of policies that may or may not be implemented as written. After all, anything speculative will likely lead to a war of factoids that only distracts from the current situation.

A skillfully done public Call On also has the advantage of reassuring onlookers that you care about the situation and the people who have been or stand to be harmed in it.

Finally Bishop Budde made an ask of him, something that involves personal reflection and growth. Note that this ask was not a demand for a specific course of action, such as an apology or the repeal of an order. The request was for a change of heart. “In the name of our God, I ask you to have mercy upon the people in our country who are scared now.” It’s significant that she asked (and later begged) for his mercy. She could have commanded him in the Name of the Lord to make a change. She could have threatened him with eternal damnation if he didn’t change his ways - though neither of those approaches are typical behavior in the Episcopal denomination. She simply, in a gentle, quiet voice, called on him to consider mercy.

One disadvantage of Calling On is that you don’t get to continue the conversation in a productive way. You have no say in whether the person takes your invitation to heart or deflects it, as we humans often do when left with disquieting emotions. The President publicly has demanded an apology from both the Bishop and the larger Episcopal Church. This in itself demonstrates that the Call On was heard. I’d posit that the reason he is so uncomfortable at this point is that he feels some cognitive dissonance. Or, more than that, heart-dissonance — the way we feel when someone holds us in loving accountability, pointing out that they believe we could do better.

The way Bishop Budde spoke to the President was exactly how Reverend Mariann delivered sermons in our Minneapolis church.

And I know that feeling well, along with that tone of loving accountability. The way Bishop Budde spoke to the President was exactly how Reverend Mariann delivered sermons in our Minneapolis church when she needed us to reconsider our motivations or behaviors and find a way to do better. She treated us with dignity, called on our common values, reminded us of our collective and individual best selves, then asked us to consider how we could live up to all that. And isn’t this the role of the clergy, to be the “conscience of the nation?” To my ears, in Tuesday’s service, she was Calling On the President as she would any member of her flock.

Interested in learning more about Calling In, On, and other productive ways to bridge the gaps in your life?