Creating an Organizational Call-In Culture: Power, Position and Purpose

Photo credit: Fizkes at www.123rf.com/profile_fizkes

In my last post I followed a chain of big ideas to get to some common understandings about calling out, in, on and off. Most of the writing on this topic focuses on the interpersonal dynamics among the complex mix of volunteers, organizers, workers, and the general public within social justice movements. But what happens when the transgression happens at work? Does this automatically go to HR? Am I tattling if I tell the person’s boss? And what if I AM the person’s boss? Or the person is MY boss? These are all questions I’ve seen on social media.

Clearly, we need to do some further unpacking of power, purpose and position to coherently respond to marginalizing behavior in the workplace. Let’s start by clarifying our vocabulary.

working definitions:

Calling Out is a public correction for a transgression. It’s useful when it’s the only way to register that you’ve been harmed by someone with more power than you, though it is also used to display righteousness by people of similar power within social justice movements.

Calling In is a private conversation about something harmful that was said or done. It requires a relationship between the “caller” and the person being called in, as well as an investment of time and emotional effort. If you really want that person to change, it may be the most effective.

Calling On is also a private interaction, but it asks the person being called on to reflect on the gap between their better self and the words or actions that the “caller” has just witnessed. It also is used to effect change, but leaves the initiative for reflection with the person who did the harm, not the witness or receiver of that harm.

Calling it Off may be public or private. It is exactly what it says it is - calling the interaction off, either permanently or with the possibility of circling back to it at a later date. It’s useful when a conversation is getting nowhere, when you realize you’re being trolled, when you need to attend to the harm that you’ve just received, or when you simply don’t have the wherewithal to take on this kind of conversation one more time.

Now that we have some common understanding about calling out, in, on and off, let’s revisit those common questions that arise in the workplace.

How Should I Respond to a Colleague’s Racist Remark in the Office?

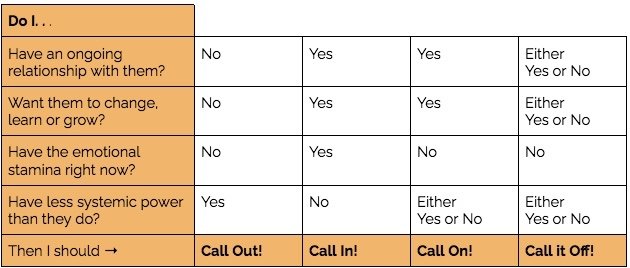

If you are the peer of a person who makes a marginalizing remark at work, you can follow the general guidelines in the Calling Out/In/On/Off Decider below, as I described in an earlier post, the same as you would outside of work. Note especially that calling out is not something you should do to a peer. Public dressing down of someone with equal or less power at work makes you seem like a know-it-all or a bully.

Calling Out/In/On/Off Decider

In fact my advice about calling out colleagues in the workplace is, don’t. Sonya Renee Taylor says that calling out is “not always the most strategically effective tool,” and that’s definitely true at work. Here’s where embodiment comes in: we know that when human beings feel shamed they are likely to get emotionally activated into fight, flight, freeze or fawning reactions. When this happens, the brain and nervous system temporarily lose their ability to learn, hear clearly, connect and care. If we want to change someone’s behavior, or help them to learn the impact of their words and actions, or change their underlying beliefs, it is simply counterproductive to put them into a defensive mode. And, because work is a place where we are evaluated, a place upon which our livelihood depends, and perhaps where our hopes for advancement reside, it’s a high-stakes place. Being called out publicly at work will definitely cause a defensive reaction.

Now let’s take a look at what to do when supervisory relationships come into play, bringing with them their interpersonal dynamics of power and position.

Am I tattling if I tell the person’s boss?

I love the wording of this question. It jives with some wisdom I learned from early childhood educators: Tattling is when you disclose something about a person to an authority because you want the person to get in trouble. Telling is when you disclose something to an authority because you want to keep trouble from happening. On the playground this might look like being mad at someone for cutting in front of you in the line to go down the slide. They’re being a jerk, but nobody is in danger. Disclosing that could be tattling – unless you have tried “using your words” multiple times and the person keeps doing it. But, if that person is pushing other kids off the slide, you should tell right away. Somebody is going to get harmed, if they haven’t already.

Diana School, Reggio Emilia, Italy

Translating this to the world of work, if it’s a matter of language, by all means “use your words” to call them in or call on them. But if it becomes a pattern that begins to fit a definition of harassment, you need to tell the boss or HR. And if some form of active harm is taking place, that also needs to be told.

It’s important to note that even if your intentions are good, but you go up the chain quickly for a one-off remark without speaking up yourself, it’s going to be perceived as tattling. Tattling is likely to cause a defensive response, rather than the reflective moment of calling on or in that could lead to a change in both behavior and beliefs.

Does this automatically go to HR?

At work, consider that HR might be what we have in place of call-outs. In most cases, it can be the channel of complaint and accountability, the place that can make sure your “ouch!” can be registered by those who need to hear it. That said, if you are in the dominant group, HR should be the backstop, not your first stop. I don’t mean to dismiss HR. It has its place, especially if harm is happening and those in power are not responding appropriately. However, if we leave conversations about equity and human rights in the domain of HR, we are consigning them to the realm of compliance. Check a box and be done with it.

“If we leave conversations about equity and human rights in the domain of HR, we are consigning them to the realm of compliance.”

Compliance can change people’s overt behaviors, but rarely makes a dent in their deep beliefs – the very source of the lasting change in systems that we need to see. Assigning all these conversations to HR (or the DEI Director) also effectively alleviates everyone else of their duty to speak up. That’s not going to change the consciousness of the organization, or of anyone in it.

What if I AM the person’s boss?

Being in a supervisory role puts you in a position of power as well as visibility. Whatever you do – or don’t do — is going to be noticed. So, first of all, you cannot let racist (or sexist, homophobic, ableist, etc.) remarks slide. This can be dicey given that a full supervisory conversation would need to be a private one. If a remark happens in a meeting where others are present, you have an obligation in the moment to at least point out that it isn’t in line with company expectations. This may seem like a small thing, but it can have a big impact. When you speak for the expectations, you are reassuring people who are wondering if you’re going to let that kind of behavior slide. You are letting everyone know that the company expectations aren’t just pretty words on paper. You are acknowledging that other behaviors happen out in the world, but that in this atmosphere, we are all making the choice to use equitable speech - words that are neither marginalizing nor hateful. This conveys an implication that the person who made the remark can choose to join in this culture, and with that you are reinforcing a culture of non-disposability.

Whatever you do – or don’t do — is going to be noticed.

You cannot let racist (or sexist, homophobic, ableist, etc.) remarks slide.

Photo credit: www.123rf.com/profile_fizkes

If your palms are sweaty and your heart rate has notched up just from reading this, take a breath now. You don’t need to have a Master’s degree in race relations to handle this. What you do need is a sense of what kind of organizational culture you want to create, and who is vulnerable within that.

Here’s a simple script you can rehearse: “Did I just hear you say _____?” (allow time for them to answer) “That’s not in line with our culture here.” Or, if your workplace is more informal, “That’s just not how we roll here.” It’s important to allow that time after asking if you heard them correctly. In my experience, people will often register some surprise at how their own words sound, and then offer a clarification or even a retraction. If this happens, just add the words, “Oh, good, because” in front of your statement of culture: “Oh, good, because what I thought I heard you say just isn’t in line with our culture here.” It’s the tiniest public Call-On, and you don’t need to skewer them for their original utterance.

“Did I just hear you say _____?” (pause)

“That’s not in line with our culture here.”

A Fifth Option for Supervisors: The “Office Call”

Because you are their boss, you then need to circle back to them to set up a private conversation - something I’m calling an Office Call. This is the place for Calling-In, to better understand their intent, and to help them understand their impact. It's also the place to make clear that there will be consequences if no change is made. As I carry out structural equity audits on organizations’ policy documents, it’s common for me to find “coaching” listed as the consequence for harassing behavior with no accountability attached.

And here’s another place where the workplace differs from a social media platform or book group: the workplace necessarily has limits around indispensability culture. If one employee’s behavior is going to cause harm to another, including causing them not to express their full potential at work, we can’t treat the person causing harm as indispensable. Non-disposability is a more realistic goal. We don’t fire people the moment they mess up; but neither do we offer a never-ending series of coaching sessions paired with paid leaves, lateral transfers, and other non-consequences.

What if I’m the boss and I’m told about something I didn’t see?

If an employee comes to you with a situation you weren’t present to see, prepare to listen.

First, listen for potential harm. That way you can tease out telling from tattling. If there’s harm going on and someone is notifying you, that’s telling and it’s appropriate. Thank them and listen for all the details you can - when and where did it happen, who was present, has it happened before? And, have there been any call-in’s or call-on’s before this?

Next, listen for what you’re being asked to do. Sometimes people will tell a supervisor as a way of seeking support. They may want to rehearse what they’d like to say to the person, or ask if you think it’s a good strategy, or make sure the remark was not in line with your culture, or that you’ll have their back if there’s a repeat of the initial situation. Other times they want to hand it over to you for further action. If this is the case, and you’re satisfied that there’s potential or actual harm involved, set up an Office-call with the person you’re being told about.

You can use the same Office-call script even though you were not in the room when the marginalizing remark was said. Simply start with “I’ve heard that. . .” or “It’s come to my attention. . .” or other phrase that lets them know that they were overheard, and that you’ve been notified. “I have heard that you said ______.” Again pause for their response, and again let them know it’s not in line with your culture. Continue with the Office-call conversation, including clarifying or assigning consequences. Of course, you must keep the name of the person who brought the situation to you confidential. Who it was honestly doesn’t matter; they are a person who was concerned about potential harm. This isn’t a tattling situation, but a telling one.

“We don’t fire people the moment they mess up; but neither do we offer a never-ending series of coaching sessions paired with paid leaves, lateral transfers, and other non-consequences.”

If, on the other hand, it sounds as though the person who discloses this to you is suffering from a bruised ego, or as Kai Cheng Thom puts it, “is more about the performance of righteousness than the actual pursuit of justice,” then this may be a tattling situation. Ask a few more questions about their motives and feelings in the situation. Does the person want to get their colleague in trouble? Particularly if they seem to want you to do a public call-out for them, you may need to educate them on why that isn’t a good idea at work. Does it feel like there’s some professional jealousy or other personal hurt feelings at play? Did the person they are reporting to you publicly correct them in an embarrassing way? You may need to help them distinguish between hurt (temporary discomfort that may lead to growth) and harm (discomfort that causes further injury or builds on generational/structural trauma). Notice the identity and power dynamics at play in the situation, and recall Loan Tran’s caution that calling in (or office calling) is not “a free-for-all for those with privilege to demand we put their hurt feelings first regardless of the harm they cause.”

If you have a strong feeling that it’s tattling, assure the person that you’ll keep your eye on it in case it becomes a pattern. And check in with the person they reported to see if there’s any support they need as well. Don’t mention the tattling to them; just that you’ve noticed some friction between them and the other person. Again, practice your listening skills.

What if it’s MY boss?

This depends on your relationship with them, your position in the company, what you want to happen, and how much energy you have for the conversation. I’ve had bosses with whom I’ve had a close working relationship and been able to have calling-in conversations, and bosses I would not have dreamed of initiating that conversation with! Bottom line: If you feel at all uncomfortable speaking to them, or if harm is happening, head to HR or your organization’s civil rights officer. Dealing with these types of situations with people in supervisory positions is an important HR function.

That said, the bosses I’ve successfully spoken to were people who welcomed feedback in general, so the subject was relatively easy to broach. In those cases I would use a similar script to the boss one above: “The other day I thought I heard you say _____.” I’d leave space for a response. Then, I would let them know the impact of those words on me, personally. I’ve recently moved away from using the term “offended,” in favor of “marginalized,” or “concerned.” Being offended is something that can happen in a free speech environment, and using that term can be interpreted as your thin skin. Saying I’m “offended” invites the other person to tell me to toughen up, or to join the club, or other deflection. But stating a concern for my marginalization or that of colleagues offers a way into further conversation.

A Further Dimension of Systemic Power

At work, as you are examining whether you are the best person to initiate a call-in or even a call-on, you’ll also need to consider the historical, systemic power dynamics at play. Where do your identities line up with the dominant culture, and where have your people been marginalized? When you’re in the dominant, don’t be surprised to find that you are often in a better position to carry the message.

“When you’re in the dominant, don’t be surprised to find that you are often in a better position to carry the message.”

For me, this is true. I know as a White woman I’ll get less blowback than Black or racialized colleagues if I bring up something that we’ve all noticed. I learned this the hard way. Once, a Black woman colleague brought up an inequitable situation to our boss in a meeting. I didn’t know ahead of time she was going to say anything, but I knew what she was talking about and backed her up immediately. I thought I had done enough. I found out later that she had been chastised for this. I personally didn’t receive any criticism or even constructive feedback at all. Now I have learned not only to offer to be the caller-in, but also to be proactive and not to wait for the marginalized person to expose themself to further inequitable treatment.

Putting our Big Ideas to Work, at Work

Now that we've clarified some dynamics of power, position and purpose at work, here's a summary chart that's organized by purpose:

Workplace Calling Out/In/On/Off Comparison Chart

Consider your Purpose, Position and Power

These are just a sampling of the kinds of questions that come up at work. I’ve created the comparison chart above to summarize the information you need to make some educated choices, and to read and learn further in this area. Remember, when we’re talking about systemic change, we’re talking about adaptive change, not a technical checklist. Your best bet is to listen to the people in your environment, try out some call-ins and call-ons, and pay attention to what happens. And, if you’ve got more questions about awkward work situations, let me know!

One last thing - if you realize that marginalizing remarks are in line with your organizational culture and need help changing that, a Cultural Ways of Being Audit is a great way to raise awareness of your culture, as well as of alternate ways of being that better align with your values. Click below for a free, 30-minute conversation to see if an audit is right for you.