Update: Leadership and the Anatomy of Calling Out, In, On and Off - Or, How Should I Respond to a Racist Remark?

Photo Credit: Andrey Popov, www.123rf.com/profile_andreypopov

Recently there has been a lot of press, sometimes bordering on a moral panic, about toxic “callout culture.” In response to this, there has been a chain of big ideas that propose alternatives to calling out: calling in, calling on, and calling off, and suggest strategic purposes for each. They have thoroughly addressed situations that happen in response to public speech, for instance, on social media, at a conference session, or at a political rally; or in private spaces such as at family cookouts, in your book discussion group, or within a volunteer social justice organization. In this article I’ll take us through the pro’s, con’s and purposes of each technique so that you can effectively lead toward a less toxic culture wherever you find yourself. Because there’s so much to say about all this, I’ll write more later.

The Chain of Big Ideas and Their Definitions

Calling Out or Canceling

Both describe the phenomenon, often on social media, of being publicly corrected and shamed for a transgression which can range from marginalizing or bigoted speech to active discrimination or quid-pro-quo harassment. Being “canceled” adds being labeled “persona non grata,” not to be recognized or communicated with - the equivalent of being shunned or excommunicated from a religious group.

Author and thought leader Sonya Renee Taylor has pointed out that the positive purpose of calling out is simply to register that harm has been done, or “the possibility of saying ‘ouch!’ loudly enough that someone can hear it.” When you issue a callout, you are not offering to continue the conversation nor the relationship. You’re engaging your community to back you up and amplify the power of your voice. Calling out has always been one of the few available avenues for those with less power to communicate this to those with more. And this brings up an important point: calling out is something that is best done if you are “punching up” toward the more powerful when you have been harmed (not just had your feelings hurt) or marginalized (not just offended).

“A call-out culture of disposability replicates the very notions of punitive justice that many human rights movements seek to dismantle.”

Kai Cheng Thom, in 8 Steps Toward Building Indispensability (Instead of Disposability) Culture, writes about callouts within the social justice community, where they are often levied at colleagues with similar amounts of systemic power, and similar goals. She defines calling out as “a culture of toxic confrontation and shaming people for oppressive behavior that is more about the performance of righteousness than the actual pursuit of justice.” She points out that this rests on an assumption of disposability, that we don’t need everyone, and are better off without some. Furthermore, she makes clear that a call-out culture of disposability replicates the very notions of punitive justice that many human rights movements seek to dismantle.

Calling In

Proposed by Loan Tran and championed by Loretta J. Ross, Calling In refers to a relational process that invites the offender into a conversation about what they really meant, why they hold those beliefs and the impact of the remark on you. It’s best done privately/offline. Tran and Ross have an excellent online class on Calling In that runs several times a year that I highly recommend.

“Other people’s interior lives are as complicated as yours.” — Loretta J. Ross

Calling In requires several things of the “caller,” including an investment of time and emotional energy, an existing relationship allowing you to initiate this conversation, and an acknowledgment that “Other people’s interior lives are as complicated as yours,” as Ross says. If you don’t have a relationship that allows a call in, you can recruit a mutual friend who can take it on - in fact, part of the decision to call in is asking, “am I the best person to communicate this?”

It also rests on a growth mindset - the idea that we never stop being able to learn, and that we often learn best through setbacks. If I believe that a person is incapable of learning or changing, it feels futile to try calling them in. But if I recall how much I and others have learned and changed, it feels worthwhile. To this day, recalling conversations that people further along the journey took time to have with me remains my biggest motivator for calling in.

Calling in fits into Kai Cheng Thom’s quest for a “politics of indispensability,” where no one is disposable, and it’s worth the work to call them into community. To me, Thom is clarifying a prerequisite for what Martin Luther King called “Beloved Community.” In the calling-in process, Ross and Tran are proposing its method. In fact, Ross has called it “this century’s nonviolent resistance.”

Calling On

Sonia Renee Taylor proposed this as a third option. Calling on allows for the future growth of the transgressor without the investment of time and intellectual/emotional labor required for a call in. The idea is to remind the person of their best Self, point out the gap between that and what they recently said or did, and then call upon them to reflect on that gap in order to live up to their best. Loretta Ross takes this suggestion and models it beautifully in her TED talk.

“In reminding the person of something admirable about themself, you prime them to avoid a shame response. . .”

What works so well about Calling On is that in reminding the person of something admirable about themself, you prime them to avoid a shame response and its attendant defensive mechanisms. You are expressing your disappointment in their actions at the same time as your belief that they are better than that at their core. As an educator, I know this as a key way of activating a growth mindset to keep students engaged in learning despite frustration and temporary failure. An added benefit of this technique is that it doesn’t rely as much on anyone’s positionality in the situation. I could call on my aunt, my boss or an elected official with this same method. And, it can be done publicly or privately.

Calling Off

Of course, you may find yourself in a conversation with someone who is trying to push your buttons, or who insists on using and re-using language you’ve requested them to stop, or who is themself in an emotionally activated fight-or-flight state, drawing a false equivalence between harm to marginalized groups and hurt to their own feelings.

“Think of it as healthy boundary-setting”

In any of these situations, it’s probably in your best interest to exit the conversation. Think of it as healthy boundary-setting, where you can decide whether you’ve called it off permanently, or if this is a temporary break and you plan to re-engage later. Loan Tran puts it this way: Calling in is for “people who we want to be in community with, people who we have reason to trust or with whom we have common ground. It’s not a . . . free-for-all for those with privilege to demand we put their hurt feelings first regardless of the harm they cause.” For the latter group, we have calling it off.

Deciding to Call Out, In, On or Off

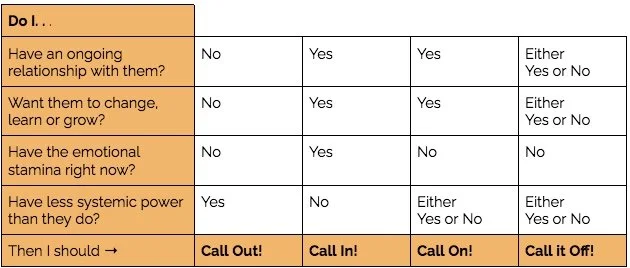

In discussing calling out, in and on, Sonya Renee Taylor asks us to select the strategically most effective tool for each situation. The Decider chart below summarizes the purposes, personal requirements and power dynamics of each to help you choose wisely.

Calling Out/In/On/Off Decider

Once you make a choice, stick with it. Each of them requires you to practice some skills, including: listening deeply, speaking frankly but kindly, staying grounded, and recognizing both current and historical power dynamics at play. As you implement this full toolbox of options rather than solely calling out, you’ll lead by example toward a more inclusive culture – whether in your family, a volunteer organization, or at a public event.

update: A manual for what to say when Calling In or on:

One of my mentors, Christine Saxman — the one who coined the phrase “loving accountability” — has co-authored a book. I knew it was going to be good. It turns out to be a detailed manual for Calling In conversations! By examining the different stages of White identity development, it explains why messages work sometimes but not always. In fact, a message that is just the right thing at one stage can be completely counterproductive at another. The book gives us a menu of do’s and don’t’s for our responses, along with a window into which alt-right messages get traction at each stage.

If you’re ready to start Calling In or On, this is a great read to ready yourself for the process!

Need some help getting started? Contact me for a free, 30-minute introductory coaching session.